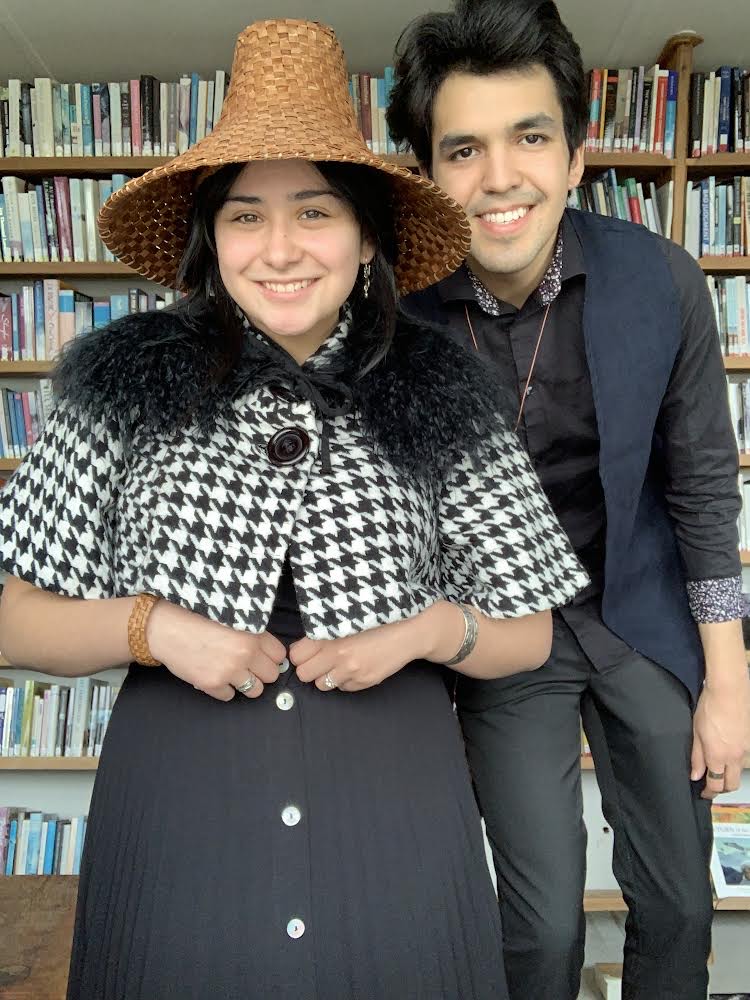

Photos: Emilee Gilpin

Clea Schooner just got back to her community in Bella Bella from a trip to Sweden where she participated in a Declaration for Indigenous Peoples across the world at the UN General Assembly Stockholm+50.

Clea, 22 years old, lives in Bella Bella and works with the Qqs Projects Society, a Heiltsuk-driven non-profit that supports Heiltsuk youth, culture and environment. Stockholm was Clea’s second UN event in the last two months.

As a part of the Wayfinders Circle, established to amplify Indigenous leadership, Clea was also a part of a panel at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York. As she navigates a world of politics, Clea says she looks to her cultural values and greatest teachers to ground her and guide the way.

‘Weighted and proud’

Sitting in the sunroom of her grandfather Yím̓ás (Hereditary Chief) Wigvilhba Wakas’s house, Clea speaks of her great grandmother Emma Humchitt, who she says has had the biggest influence on her life.

“She was a language speaker. She was very involved in our culture… I don’t think there was a community event that she didn’t go to,” Clea says. “She was that kind of person. She always wanted to show up and support her community.”

Clea was fortunate to have her great-grandparents alive when she was younger, mentoring her and shaping her during “key years you really figure out your values, beliefs and identity,” she says.

“There were so many things my great-grandmother taught me, both while she was alive and long after she passed too,” Clea says. “I always want to do things in a gentle and constructive way, which is what she showed and what she talked to us about.”

Clea remembers when she opened the children’s series during the historic Gvúkva’áus Haíłzaqv (Heiltsuk Big House) opening in 2019. She was wearing her great-grandmother’s dancing regalia and she felt her presence strongly in her, Clea says, as she navigated a world of emotions.

“Everyone was there. It felt really weighted, but also really proud,” Clea says. “It was so joyful to celebrate with our people, to have a ceremonial place in our territory, to practice our culture, but also emotional that it was banned… how much people suffered for it… it was very mixed emotions, very confusing.”

‘It’s just in us’

Clea says it felt like a part of her was missing before the Gvúkva’áus Haíłzaqv was built in her community.

“That part of me was restored, rejuvenated,” she says. “I feel like I wouldn’t be in the position I’m in if it wasn’t for this Big House. I felt like all my life I was only allowed to whisper, and now I feel like I’m allowed to speak.”

She entered the world of politics without really realizing.

“I blinked and now I’m in politics,” she says. “Every Indigenous person is born political. No matter what you say or do, it’s going to be taken as political, so I’m just making a career out of it now I guess.”

Clea says she learned more about the art of diplomacy at the UN events she attended.

“I learned how to be diplomatic. This world has changed and shifted so much when it comes to Indigenous Peoples post-contact. In order for us to adapt, we have to integrate and to do that we have to be very diplomatic,” she says. “We have to look through things from an intercultural perspective. Never working against, always working with.”

Clea has been witnessing and learning from other Indigenous organizations fighting for their rights, and to be seen as equals, she says. It deepened her appreciation for the global solidarity and struggle of Indigenous Nations.

“It was a really empowering experience, a really humbling experience,” Clea says. “We all have so much intergenerational trauma and have been affected by colonization. You really understand Indigenous issues exist on a global scale and you learn different tools on how to work with these issues.”

It was important for Clea, during her short visit to Sweden, to address the climate crisis she sees directly impacting her community.

“It was important for me to address the fact that for isolated Indigenous communities, it’s not a ‘what if?’ question of climate change, it’s a crisis now,” Clea says. “Our sea levels have risen, our temperature in our waters has gone up.”

The wellbeing of the ocean directly ties to the wellbeing of her people, she says, holding incredibly significant cultural value.

“Our herring, for example, they’re so sacred to us, they teach us reciprocity… it’s not an easy trek coming back, but they always come back and feed us, and we give back,” she says.

Clea says before, she didn’t think she wanted to have children, never imagining “bringing kids into a world where they’re going to have to fight this fight tenfold because of the lack of representation of Indigenous Peoples in our environment systems.”

A conversation with a dear friend, Cúagilákv (Jess H̓áust̓i), had her rethink her stance.

“But then I thought about it and I actually had the best advice from Jess Housty, who said that if there were any children that could impact our society and our environment, it’s Indigenous children. And if I raise Indigenous children with the values and beliefs of our culture, then we can reintegrate and regenerate our systems because we know of resistance and we know of resilience and that’s something that isn’t taught. It’s just in us.”

Meeting the right partner after that advice was an indicator for Clea that while she might not be ready now to have children, it’s a possibility. Her fiancé and her are busy prepping for their traditional wedding which will be held in the Heiltsuk Big House during her papa’s potlatch next summer, 2023.

How I fly

Clea’s great-grandfather, Bob George, is the son of the late Chief Dan George, a famous Tsleil-Waututh actor, political activist, writer. Clea, who’s also a writer, attributes the passion to that side of her family, she says.

Writing, for her, has been a way to process, to “take it from internal to external and let it go,” she says. Over time, Clea shares, she has come to welcome hardships, understanding that there are lessons embedded in them.

“I welcome them, I don’t seek them out… but I know that whatever was thrown at me was made for me,” Clea says. “I was diagnosed with complex PTSD at 16 so I really learned how to understand my body, understand my mind, understand my spirit through a cultural and a Western lens… with counseling and traditional practices. I feel like every step of this journey, hard or not, was made for me, and I wouldn’t ever trade it.”

Clea takes out her phone and brings up a list of her poetry. She scrolls through a few, reading their names and lands on ‘How I fly’ and shares.