In the late 1990s, the David Suzuki Foundation started stirring up some trouble in the environmental community. Through their work with Indigenous communities across the world, they realized that if humans wanted to sustain their existence on the planet, the world must adopt an Indigenous-rights-based approach to environmental conservation.

Indigenous-led conservation wasn’t the popular opinion among other environmental groups at the time, many of whom were busy setting up blockades (sometimes muddying up ongoing agreements and negotiations), often without the consent of the Indigenous Peoples whose territories they claimed they wanted to protect.

At the time, Jim Fulton had been a member of Parliament from the Skeena (a region the size of France) riding for over fourteen years and he had strong connections with First Nations along the coast.

“Jim Fulton was familiar with the coffee tables in every small community in that area,” says Tara Cullis, one of three main founders of the David Suzuki Foundation (DSF) founded in 1990. Fulton advocated for supporting Indigenous sovereignty at the time, David Suzuki, the foundation’s second co-founder (and the organization’s namesake) adds. “If we can support First Nations’ drive for sovereignty or control of their areas, they will do a hell of a lot better job than we can,” Suzuki remembers Fulton saying at the time.

While fighting to protect forests and fish populations in other regions, from California to Oregon, in 1995, the DSF decided to take a good look at their own backyard, Cullis says. “We started producing a lot of reports,” she says. The reports focused on the impacts of forestry, sustainable fisheries and salmon management. “We looked at 12 sustainable production fisheries to see what they had in common and that was limited size, local control, and local ownership.”

Focusing specifically on the BC northwest coast, Cullis, Suzuki, Miles Richardson (the DSF’s third founder), Fulton and other interested parties realized any kind of meaningful conservation needed to involve empowering First Nations who spoke with some semblance of a unified and therefore a voice that couldn’t be ignored.

Richardson started thinking, strategizing and making plans. The foundation dedicated nearly half of their staff, working on reports to demonstrate the need for different forestry models and ecosystem management plans in the region. But there was more work to be done to nurture relationships and build trust. Cullis, it was decided in 1997, would visit coastal First Nations communities, to listen to how communities were experiencing logging and fishing pressures, and if they had any solutions the foundation could support.

“I woke up in November, 1997, to hear Edwin Newman’s voice from Bella Bella,” Cullis remembers. “‘Environmentalists are not welcome in our territory,’ he said, and my heart sank. That’s when an environmental group had barricaded a logging road without asking the Heiltsuk’s permission.”

Cullis was discouraged, but she had known Newman, a respected leader from the Heiltsuk Nation, so she picked up the phone and called to see whether or not the community would make an exception and be open to speaking about coastal unification. “He went quiet as he thought about it and then he said, ‘I think you should come,’” Cullis says.

So she packed her bags. In January, 1998, Cullis asked for invitations from other communities and began her trips to Bella Bella, Bella Coola, Klemtu, Hartley Bay, Kitimat Village, Metlakatla, Prince Rupert, Lax Kw’alaams, Skidegate and Masset. “I must have made over 200 trips,” she says.

“We Want to Save this Ecosystem”

What Cullis heard during those trips was that in order for the communities to get behind conservation strategies, they wanted to address the ways their people had been economically exploited. “We need jobs, and then we can talk about conservation,” Cullis remembers being told over and over again. Five women, who called themselves “The Spice Girls,” got to work.

The Spice Girls included DSF Liaison Lula Johns-Penikett from the Whiteriver First Nation in the Yukon, Roslyn Kunin, former head of the Vancouver stock exchange, Jane Woodward, a lawyer and judge (expert on the ramifications of the famous Delgamuukw case), and Joan Ryan, who led the participatory action research process of community development, and Cullis.

With the help of the Spice Girls, the DSF turned itself into a community economic development shop. “We opened an office in Prince Rupert, held gatherings, funded job creation projects in each village, trained CMT architecture experts throughout the coast, organized seafood inventory, salmon stream studies, ooligan work, co-op stores, hydroelectric projects and mapping GST training projects,” Cullis says.

But these efforts weren’t without pushback from some government officials and other environmental groups. “Back then, the attitude of most environmentalists was to protect areas by making them into parks,” Suzuki adds. “In a park, humans go to visit. It was an approach that denied the reality that humans have lived in these areas for thousands of years.”

Cullis found out about a First Nations Summit taking place back in Vancouver in 1999. They wanted to take advantage of this gathering and called a meeting with some of the Chiefs of the villages with which they were working, to discuss forestry concerns and the potential of a collaboration. Art Sterritt and Patricia Sterritt from Hartley Bay spoke up at this meeting, Cullis remembers well, saying, “The most important thing about this meeting is who is in this room right now. Many of us know each other, but have never met.”

Gerald Amos from Kitimat chimed in saying, “We have the same problems, so maybe we have solutions too that we could share.” Conversations continued throughout the Summit, and Chiefs decided to hold another meeting.

‘The Turning Point’

The first “Turning Point” meeting took place on March 4, 2000, in Musqueam. It was the turn of the millennium, and each Chief took a turn sharing their stories and vision for the future.

Cullis and their team had taped various international declarations all around the walls — statements of solidarity from different Indigenous communities across the world. From Japan to Southeast Asia, to the Amazon and Andes, place-based peoples were using similar terms and language to discuss their fight to protect that which they were an intricate and interconnected part, from industrial development, forestry, mining, agriculture.

Roger William, who was one of six Tsilhqot’in chiefs at the time, from the Xeni Gwet’in community, was invited to this gathering of coastal leadership. His nation had written a declaration similar to those pasted across the walls, and he was there to answer questions about his peoples’ process, Cullis remembers.

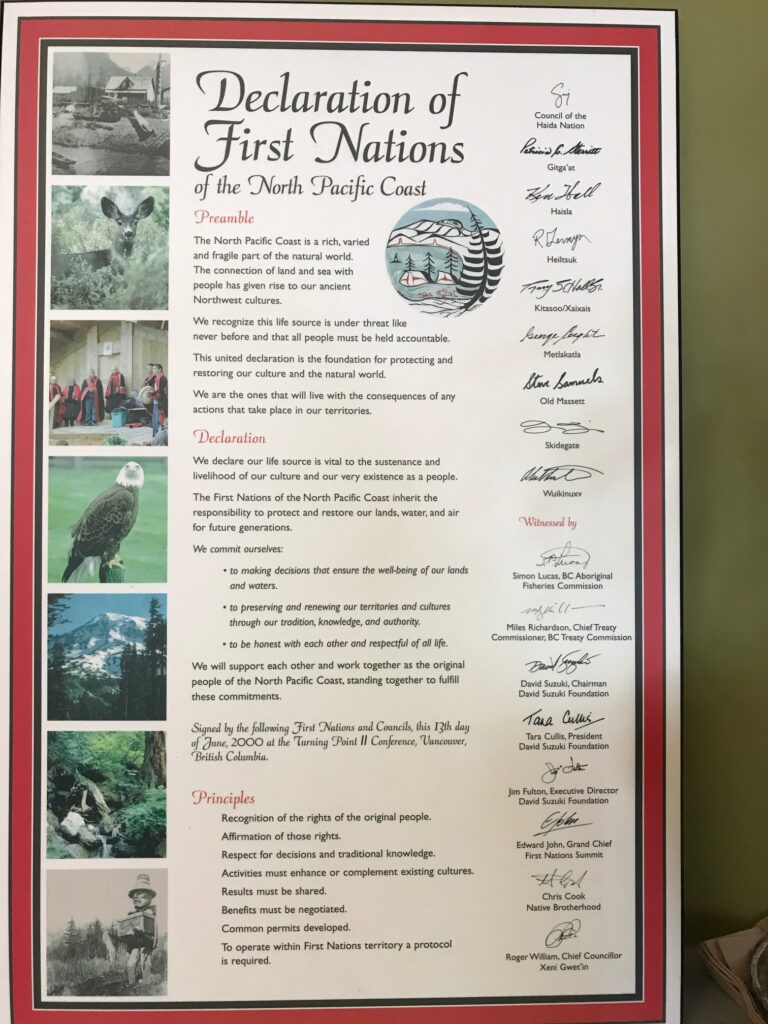

During the second day of the first Turning Point conference, Gidansda Guujaaw from the Haida Nation led the writing of a new declaration. The DSF was asked to write up a list of guiding principles, and leadership headed home to their villages to have the declaration ratified.

The second meeting was held three months later, at the UBC House of Learning, Cullis recalls, where Chiefs held a signing ceremony for those who were ready to sign. The group requested government-to-government-to-government meetings to set the terms of reference for land-use planning across the coast.

“We sent letters to the Prime Minister and the Premier of B.C., and presented a report about ecosystem-based logging, called ‘The Cut Above,’” Cullis says. The third Turning Point meeting was held in Prince Rupert one month later. “These meetings were hot and heavy,” Cullis says, smiling at the memory.

Garry Wouters, hired by the DSF at the time, presented a strategy for the new agreements. The interim measure strategy was adopted unanimously by all communities, Cullis says, including both Tribal Councils.

Less than a year after the first meeting, general protocol agreements — affirming that ecosystem-based management should guide land-use planning — were presented to Gordon Wilson, who was BC’s Forestry Minister.

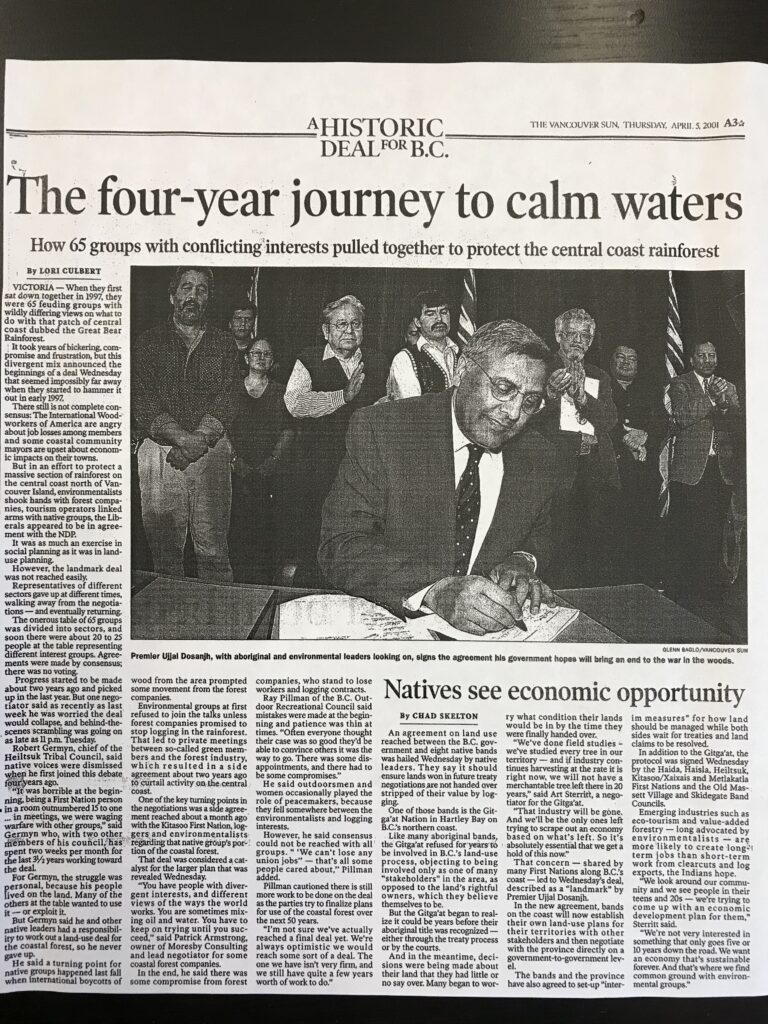

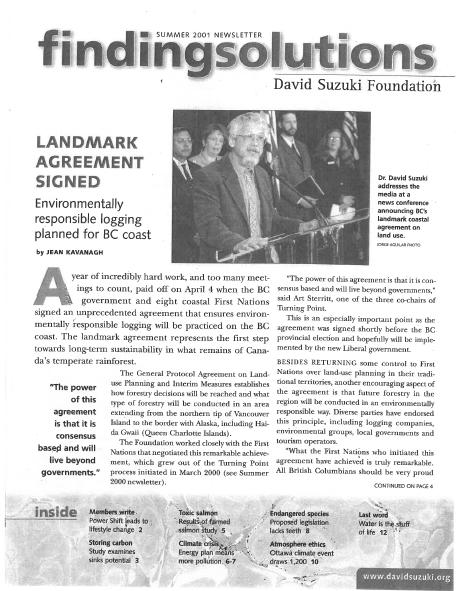

On April 4, 2002, the premier signed two different agreements — one involving the Turning Point (not yet named Coastal First Nations) — which was called the “general protocol agreement on land-use planning and interim measures.”

“It was signed with eight coastal First Nations, just 13 months after the first meeting,” Cullis says. “On that same day, the landmark decision was signed between 65 representatives from environmental groups, logging industry, tourism operators, and First Nations.”

‘These Relationships are for Life’

The DSF helped raise as much money as they could, Cullis says, and then wanted to step away, leaving it as an independent organization with its own offices downtown (until then, operations were being housed at the DSF offices). “There they changed their name to Coastal First Nations (CFN), took some staff and contractors, and they have been working hard to protect the coast ever since,” Cullis says.

“It was a big learning experience for all of us,” Suzuki chimes in. “We had to learn protocols, and they would vary from village to village. Tara established a strong sense of trust over time, which was very important to the project.”

Cullis says she’s proud the process only took two years. “Sometimes, I would be the only woman in a circle of men… who hadn’t asked for my presence,” Cullis remembers. “They were pleased to see me, but they said — ‘okay, white men have come and they’ve taken our fish, our trees, our children, our language, and tried to take our culture… what have you come here to take?’”

“I couldn’t blame them,” Cullis continues. “That’s quite right. So one has to be patient and just wait and see how people feel after they said what needs to be said.” Cullis says she traveled to each community alone, intentionally, and only when she received an invitation.

“It was a turning point for me,” Suzuki adds. “I learned how Indigenous relationships to the land are fundamentally different — their whole histories, cultures, the very meaning of why they’re there, is told to them with the relationship with the land.”

Once the coastal nations continued leading their own government-to-government-to-government relationships and negotiations, the DSF vowed to support, but stepped away.

Other environmental groups asked the foundation about their “exit strategy,” Suzuki remembers, to which he responded, “once you work with First Nations, there is no exit.”

“These relationships are for life,” he says. “And I thank every community that has struggled to protect their culture and language, because they are the repository of the only way of seeing our relationship with the world and how we can live in it, forever. They’re the only ones that can teach us.”

Join us for more CFN Anniversary stories at our new anniversary webpage, and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.