As Yím̓ás (hereditary chief) Wigvilhba Wakas (Harvey Humchitt) remembers the village of his childhood, he weaves story into air, invoking memory of a bustling thriving diverse community fueled by the spirit of wild salmon.

Today, it takes Harvey an hour to get to Namu on his boat, but growing up, it took his family about three hours, packing all the stuff they needed for the summer.

In 1883 the first cannery was built under the name Namu Cannery Co., sold to the company BC Packers in 1928. In 1909 a saw mill was added and by 1949 the site had five canning lines, bunkhouses, a rec hall and school. The site burnt down in 1962, but was quickly rebuilt, operating as one of the most modern canneries of its day until it permanently closed in 1970.

The Namu Harvey and many of his friends and family remember was a busy bustling very much alive place — it had multiple villages with bunkhouses, a road, a bridge, floats used by fishermen working on their nets, a cannery, a restaurant, a rec hall, a small bowling alley, a post office, general store, a school.

Many families from Bella Bella and all across B.C., would pack their families up in the spring and move them to Namu for the summer months. The men would be fishing, the women working in the cannery. Kids weren’t allowed to cross the red line at the boardwalk, but were busy in vacation school or swimming at Namu lake.

“The population could explode to about 1,500 people at the most… we had people from all over — Rupert, Kitimat, Klemtu, Bella Coola, Bella Bella, the lower mainland,” Harvey remembers as he drives his boat from Bella Bella back to visit the old run-down site, pointing out his favourite fishing spots along the way. “When people went to work at eight in the morning, there was a parade of people walking to work… it was quite the time, it was quite a gathering place.”

Some people, like Harvey’s brother, remained with BC Packers for over 30 years, loyal to the entire fish operation and the community on the harbour. It was a good company, Harvey says, they took care of their employees and provided activities and entertainment for whole families.

“BC Packers used to keep Namu in really good shape. They took care of the board walks and all that. They used to have a traveling band Taller O’Shea that would come through in the summertime. We had a big dance party, 2-3 days of celebrations at the community hall,” Harvey says.

“There was a really nice store in the village too, they kept it well supplied. There was a meat department, produce, fresh baked goods every day, all the marine equipment you needed… but it shouldn’t have been left like this.”

‘It never should have happened’

When Namu shut down, Harvey says, “they left everything.”

“They just abandoned everything,” Harvey says. “Where it used to be a thriving community, fully involved with the salmon industry, now it’s just a pile of garbage.”

Harvey coasts up to the shore. He hasn’t been back in four or five years and everything is in worse condition than he remembers. He ties his boat to a rock and walks through the remnants of the ruined buildings, crunching over broken glass and metal.

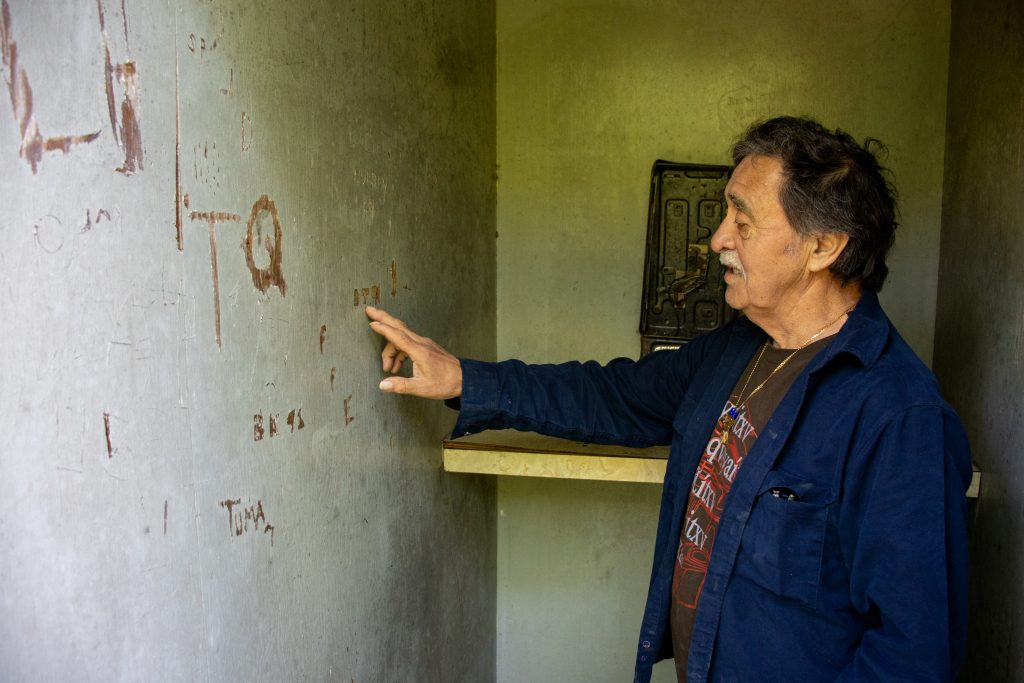

Harvey smiles and laughs at fond memories that arise as he makes his way through the general store picking up trashy romance novels, traces his finger along the names scratched into the wall of the old phone closet, recognizes a few of the names on old invoices. But as he continues on and enters new rooms, he quietly gasps “wow,” “god,” “hoh,” quietly pensive and “full of sadness,” he says, at the renewed realization that a plce once so precious has been left in such a state.

They were days of “taking your money and running,” Harvey says. He saw it happen with logging companies too. He’s visited logging camps with trailers left, full of bunks, trucks with keys in the ignition, everything abandoned and forgotten.

“That was the way they operated in those days, but it never should have happened.”

From the outside today, Namu looks like a dead forgotten pile of rubbish. But underneath all of the derelict discarded materials are living memories — fond reunions at the start of every summer, lines of people processing fish, the children running around the boardwalk, the boats arriving to the docks, the ocean lapping onto the shore — a hopeful, productive, stunningly vibrant place to be alive.

“People made friends here, became good buddies, had their first crush, fell in love,” Harvey says. He met his first girlfriend at Namu one summer — a Dutch girl named Marian whose father was a welder. He remembers her strikingly blonde hair and when she first asked him to meet her parents.

Marian would have lived in the non-native village, while he lived in the native village, specifically unit 12, where his family returned every season.

“It’s fallen to the ground now, it’s not standing anymore,” Harvey says. There was also Jap-town, where the Japanese workers lived. While there were racially segregated living spaces and bathrooms in the facilities, Harvey says eventually everyone came together.

When he was old enough, Harvey worked at Namu, starting off separating salmon eggs and salting them, then worked his way into the cannery, unloading salmon.

“We used to unload 120,000 pieces a night,” Harvey remembers. “We’d go through and unload it, fill the cannery and then the next night most of the fish would be processed. We produced a lot of canned salmon.”

He believes it was one of the most modern canneries in B.C. at the time. And although he doesn’t know exactly why it was shut down, he suspects it could have threatened business from other canneries down the Fraser River.

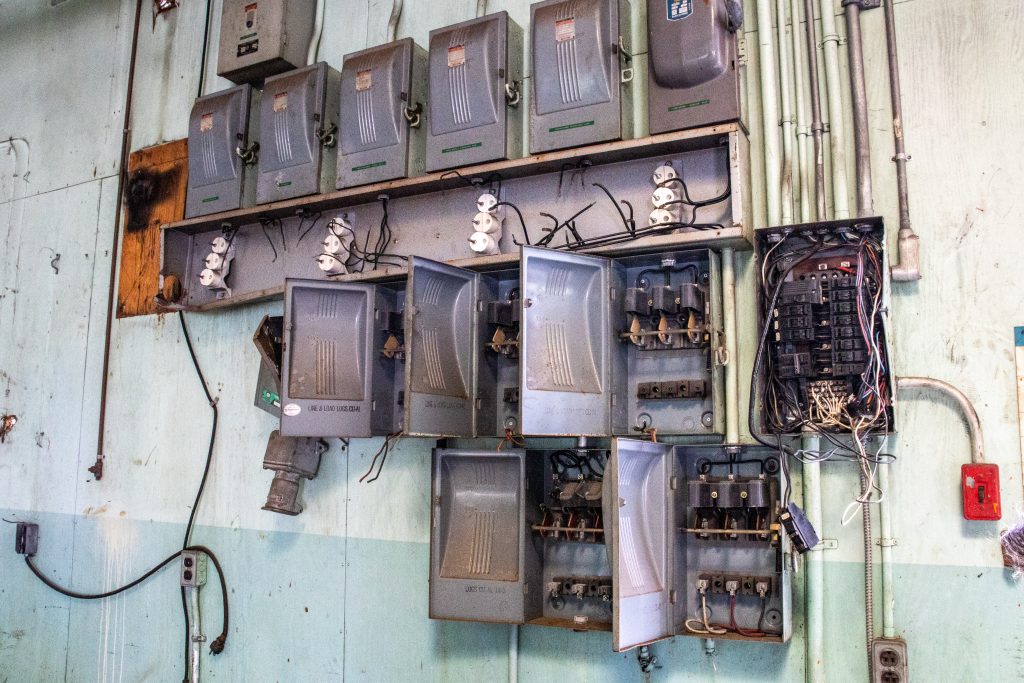

Namu today is an environmental catastrophe with an eerily post-apocalyptic feel. Massive metal storage boxes slump into the water, or hang on by a cord, waiting to drop in and join all the other waste, plastic, metal and garbage that had been dropped, broken or blown into the depths below. Abandoned buildings full of broken glass and debris shelter skeletons of rooms of discarded materials and memories.

‘There’s such history to the place’

Long before Namu was a bustling thriving summer village site, it was an old Heiltsuk village. At low tide, there’s a visible Heiltsuk fish trap in the area, and nearby is where the Nation buried over 140 ancestral remains they repatriated from Simon Fraser — including a human remains of one of their ancestors from over 5,000 years ago.

The Heiltsuk Nation has conducted two environmental studies on the site, one which estimated $10 million needed to clean up and restoration, another done ten years later which estimated $30 million, Harvey says.

“I can see where it’s going to cost money, but someone has to do it,” he says. “They should level things off and clean it up, get rid of the contamination in these buildings, get all of these things on the counters and floors cleaned up… it’s a terrible mess.”

Harvey would like to see Namu serve as a marine centre, used for ecotourism, and/or made into a heritage site. He’d like to see it restored to the rightful owners, the Heiltsuk people, but it’s hard to believe that the community should foot the bill. Chief Wigvilhba Wakas wants the people responsible to to clean up the mess left at Namu.

“There’s just such history to this place,” he says. “It’s important for us as Heiltsuk people, to maintain and protect our lands and water. When you see things like this… companies that come and make their money and then leave everything, it’s not a good scene.”

On the way back to Bella Bella, Harvey comes across a pod of humpback whales bubble feeding as he has many times before in his life. He turns his boat off and glides silently nearby, pointing to and following behind the large circles of bubbles that would suddenly appear before the humpbacks breached the surface, their massive mouths catching the fish caught up in the bubble swarm.

His people deeply care for their territories, he says and are involved in many projects, turning things around and making them right. He hopes something can be done at Namu to restore the memories resting in his ancestors’ old village site.