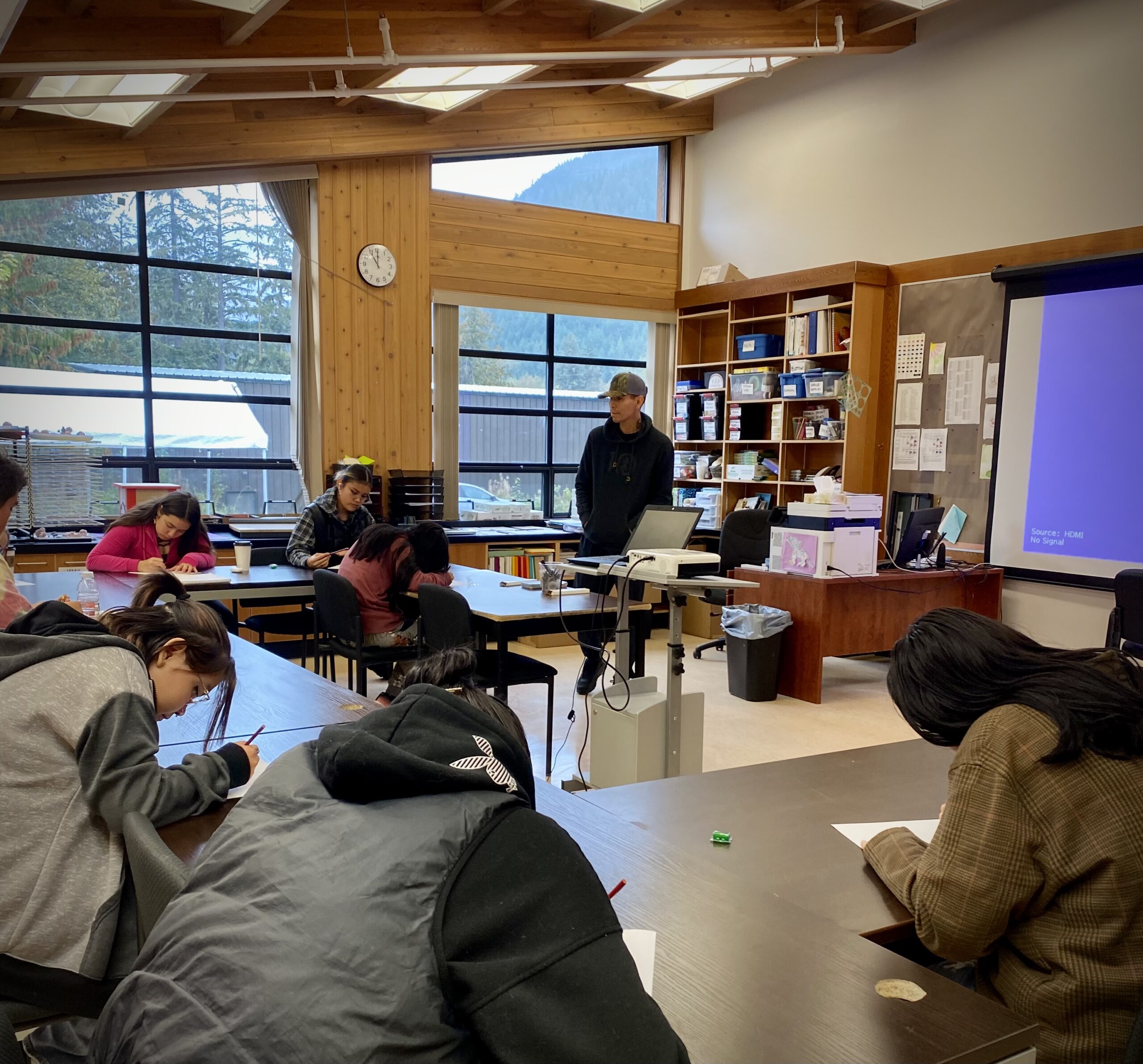

Lyle Mack is often asked how he keeps his class so quiet. He covers the rectangular window of the door with a printed photo of Nuxalk masks. Inside, his students listen to stories of Nuxalk ancestors and breathe life into their legacies through their own practice.

Lyle’s an art teacher at the Acwsalcta School in Bella Coola, Nuxalk territory. When he’s not spending time with his family or hiking his homelands, he’s in his carving shed working on projects, designing, painting, researching. He aims to light a fire within his students, connecting them to the long tradition of art and talent to which they belong.

“We’re looking at Nuxalk art first, not the other way around,” Lyle says, sitting in his class after hours while he visits with his dad. “These are just my favourites,” he waves to the photos of Nuxalk masks taped to the walls of the room. “I could have a whole room full of masks.”

Lyle teaches grades 8-12. In his first class, he talks about the people he comes from — who his grandmother was, his grandfather, about Mabel Hall, about how “every one of them was an artist,” he says.

“It’s in our DNA. I talk about our stories,” Lyle says.

It’s important to inspire the students, to remind them of where they come from, to see themselves in it, in order to hold their attention and interest.

“People say our art is never going to be like our ancestors, but how could they say that? I got four different super people I come from… If you really learn it, learn how creative they were with everything,” Lyle says.

“That’s all we’re doing is carrying on their work,” says Alvin Mack, Lyle’s father, and one of the most celebrated Nuxalk artists today. Alvin also taught at the Acwsalcta School for 21 years. “This is the way I seen it when I came in… first, you have to understand the culture.”

“This is what they can learn here. This is what they get from this room,” Lyle responds.

The more you understand, the stronger your art

Like his father, Lyle attended the Freda Diesing School of Northwest Coast Art at the Terrace campus for two years after completing the Visual Arts program at Camosun in Victoria.

“I went up North and they’re like, you gotta do our style, you already know your style, do ours. I understood the concept too, because that’s what my dad taught me when I went to Victoria — the more you understand about art all over the world, it’s only going to make yours stronger,” he says.

Nuxalk art, style and form are distinct in many ways, from the use of blue paint to the humanoid of the masks, Alvin Mack says in a separate interview in his carving shed. Lyle says he sees the difference in “the realism, the depth” of Nuxalk masks.

The more Lyle hears about and researches Nuxalk and other art and design techniques, the more encouraged he is to pass on what he’s learning. He hopes that his students will one day take over his job, that’s how he knows he’s doing what he’s meant to, he says.

Lyle shares other local artists’ work as well, like Nuxalk artist Danika Saunders who has grown her business drawing, designing and doing traditional hand-poke tattoos, based in the valley. He posts photos by Haida artist Corey Bulpitt on the wall of his class and talks about the ways Indigenous artists are pushing the limits, expanding on their ancestors’ visions.

‘It’s in our children’

Lyle has been teaching his classes about Rembrandt, a famous Dutch Golden Age painter, “all the pigments he would get, how special they were, how rare they were back then,” Lyle says. But he’s also speaking about the materials sourced from Nuxalk territories, hiking around and working with the shop and metal teacher who has also been providing culturally-relevant classes, teaching students how to make mini copper shields and shape stones.

“Sometimes we don’t realize how far we are ahead in an area. I see changes with Josh’s program and with mine, what we can weave together,” Lyle says. He felt like it took a long time to get to where he is, to have an appreciation for the way he teaches art, inspiring a new generation of Nuxalk artists.

“Everyone is super talented,” he says. He sees it in them, their focus, passion and drive. “Now that they have that foundation, they’re all good painters. ‘Now you look at our masks,’ I tell them, ‘all the paint that’s on them, that’s your belonging right there, that’s why you can do what you’re doing.’”

While technology can be a distraction, keeping youth from being outside, doing what Lyle and his siblings did growing up hiking their mountain, fishing, canning, hunting, carving, drawing, it can also be used as a useful tool, he says. He often gives the students a 20-minute break when he sees they’re losing focus, tells them to do what they need to and then comes back to the lesson.

“You got your phone, that’s your library, it can be an amazing tool if used properly,” he says. “Now that they are getting a head start, it’s these last years of encouraging them to do something with their life. It’s in our children, just like the Elders said.”