Trigger Warning: This story contains information about a missing Indigenous woman that may be triggering for some readers. Please read with care.

It’s a rainy Friday afternoon. After picking up a coffee from the local coffee shop in Masset, Monica Brown parks her red car, that has a picture of her only daughter’s face on a missing person’s poster, in front of her house. She opens the door to a warm home and settles in at the island.

“I’m from Old Masset. Both my parents are from Old Masset. My dad’s mom and my mom’s dad are from Old Masset,” Monica says, introducing herself in her two Haida names. “My daughter went missing on March 21, 2020. The last time I saw her was on March 20, when she said goodnight.”

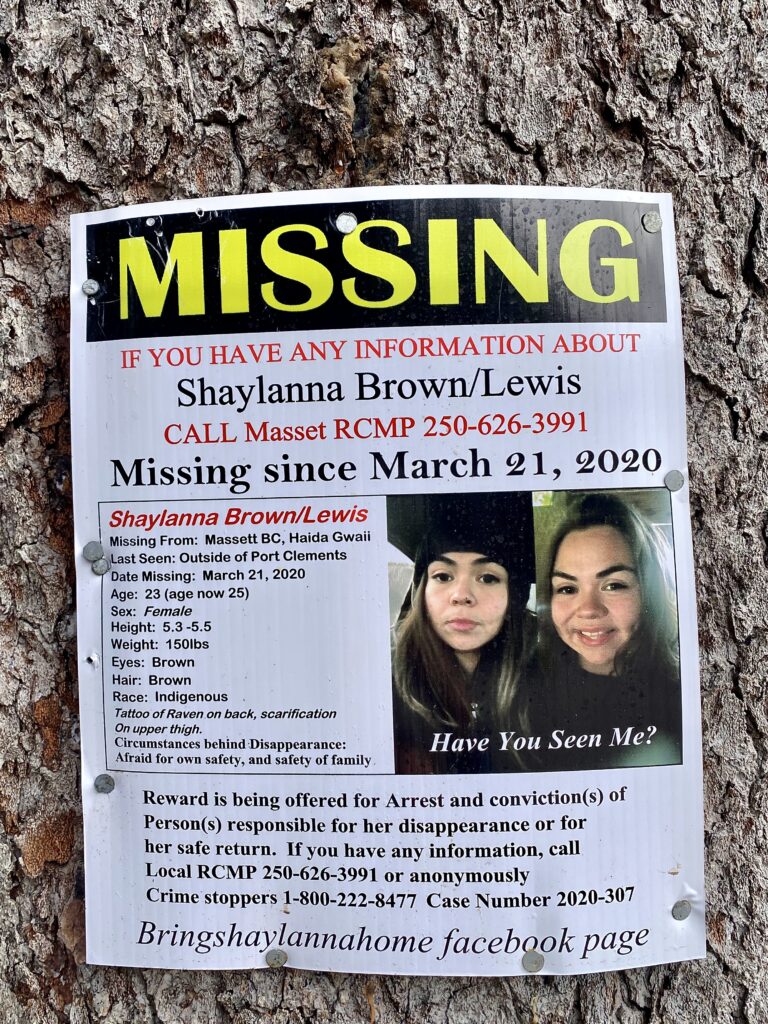

Shaylanna Lewis was 23 years old when she went missing in 2020, not too long before her April birthday. She’d be 26 now, her mom says. She’s been replaying the story over and over, in her head, with her two sons, with the RCMP, with whoever has been around to listen. She does it because “she wants more awareness” around bigger issues she believes are connected to her daughter’s case, and because she wants to encourage anyone who might know anything, to “speak up.”

The night before Shaylanna went missing, she was hugging her mom and apologizing for “bringing trouble.”

“I told her, ‘you didn’t bring trouble, it was here already,’” Monica says. Her daughter was afraid at the time, she says. She felt like she was being stalked and harassed, but Monica didn’t know who or why.

She had been going out for long walks, Monica says, she liked to stay active, she could go really far and fast. On that morning, she left earlier than usual and she never came back. She left her cell phone at home.

“We reported her missing because she was afraid for her life,” Monica says. Shaylanna was last seen near Port Clements, she says, and weeks later police found a part of her backpack and some of her clothes spread out, but none of it added up for her mother.

‘She always danced’

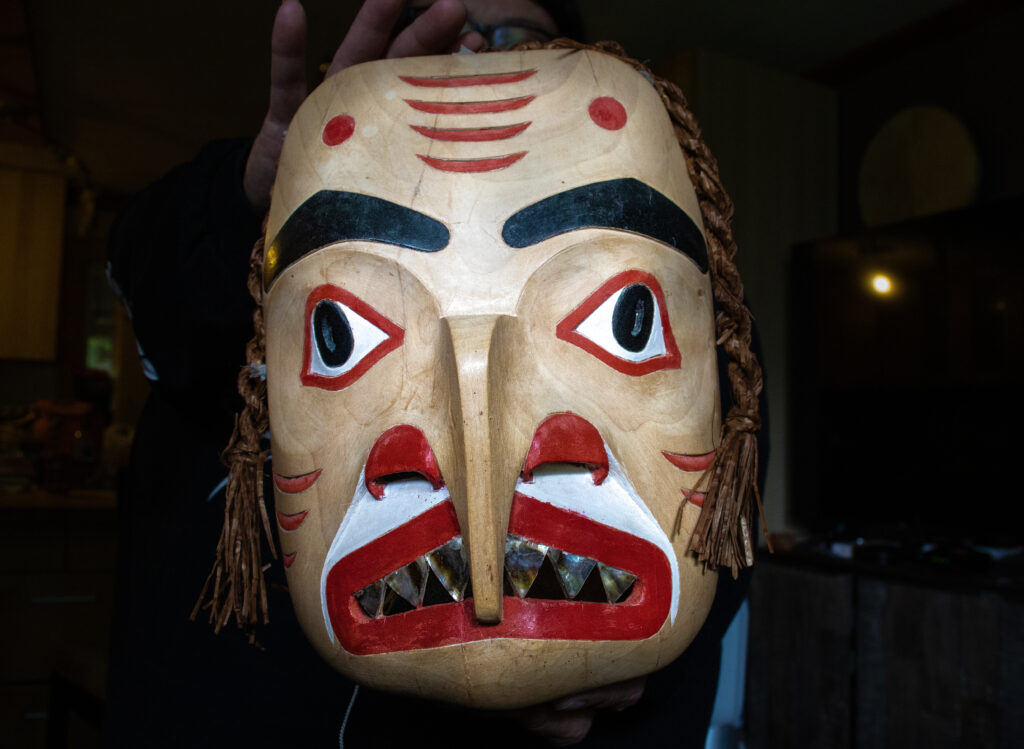

Shaylanna was a part of the Tluu Xaadaa Naay dance group in her home of Masset.

Shaylanna was a part of the Tluu Xaadaa Naay dance group in her home of Masset.

“Everything was about culture, singing, doing it right,” she says. Her daughter challenged her all the time, she says, but in a gentle way, with questions. “Do you really think that mom, or are you just colonized?,” she’d ask during their walks at the beach.

“I went to day school, my parents went to residential school and their parents went to residential school… so many generations,” Monica says. “She always challenged my thinking and we always talked about our spirituality.”

Shaylanna was a mask dancer, her mom says, and she was often practicing.

“She was practicing how to get lower and lower for the raven’s dance, how to be better and more theatrical,” Monica says. “She’s an artist too… she made her own cedar paper and things like that.”

‘I was grasping to humanize her’

The days, weeks and months that followed Shaylanna’s disappearance were extremely difficult for her family. The RCMP took her computer and phone to search for any evidence of where she could have gone. They came back about a week later with one of Shaylanna’s writings from her computer and told her family they thought it was a suicide note.

Monica and her son were shocked. It was just one of her “dynamic writings,” she says, nothing like a suicide note. They told police not to come back unless they had real evidence, a body, DNA sample, dental records… “Those are the only things we’ll accept as conclusive,” Monica had said.

Shaylanna went missing right as COVID-19 spread across the world. There was a lot of fear around being out and around big groups, with serious efforts to keep loved ones safe. Some people went out to search for Shaylanna right away, others went when they could, a small and tight-knit community rocked by the news and confused by the many stories that started to swarm about.

“I have people that came beside me right away, they’re still there,” Monica says. The Search and Rescue Program wouldn’t go out to look, she says, and police were telling people not to go search, potentially putting themselves at risk and complicating a case which they had little capacity to deal with.

Monica felt like her daughter was painted as a “little girl out in the wilderness where she doesn’t belong,” but she knows Shaylanna as very intelligent and comfortable on the land.

“The first year, I was really grasping to humanize her,” Monica says. “I did a lot of public posts… angry, attacking people, talking about colonization and the conspiracy of silence. I felt like I was doing it to piss people off so that they would react and give her back.”

She was reacting emotionally, she says, desperate, scared and confused by everything she was hearing, or not hearing.

“There was so much gossip and rumours,” Monica says, some more harmful and impactful than others. She has gotten reports of bodies found and held her breath for weeks until it has been identified, not her Shaylanna, she says.

There have been reports of potential sightings in other cities as well. Monica has taken off, driving around Prince Rupert and Vancouver, chasing around the shadow of a story, hoping that someone will see the face on her car and maybe know something and reach out.

Break the silence

A reward of $60,000 has been set for “the arrest and conviction of the person potentially responsible for her disappearance.” Monica says she’s sold off household items and gone into debt taking trips to search for her daughter. She sells her jewelry too, doing what it takes to make it all work as she’s off on stress leave, she explains.

It’s not just a story about Shaylanna, she says — it’s a story about Indigenous people dealing with substandard support services and a culture of suffocating silence.

“The social norms are to keep quiet… we’ll keep silent about anything we know,” Monica says. “Especially for Indigenous women… you take the beatings, being called down, worse… there have been a few murders here, but they’re often deemed as accidental…nothing suspicious.”

“Silencing can’t take place,” she says. “It still takes place. And people don’t talk about what they or their loved ones have gone through, they stay silent. Knowing how much we have been silenced… I want that out… people have the right to deal with what they’re going through… Shaylanna isn’t the first one.”

Monica won’t give up searching for her daughter or searching for answers. The hashtag #BringShaylannaHome is being used across social media to continue to spread awareness of her story.

“I can feel her, I just can’t figure out where she is,” Monica says softly. “That’s why I go and look, because she needs to be able to see or hear… maybe even one person will see that missing person poster or posts on social media and might be able to make a connection, help in any way.”